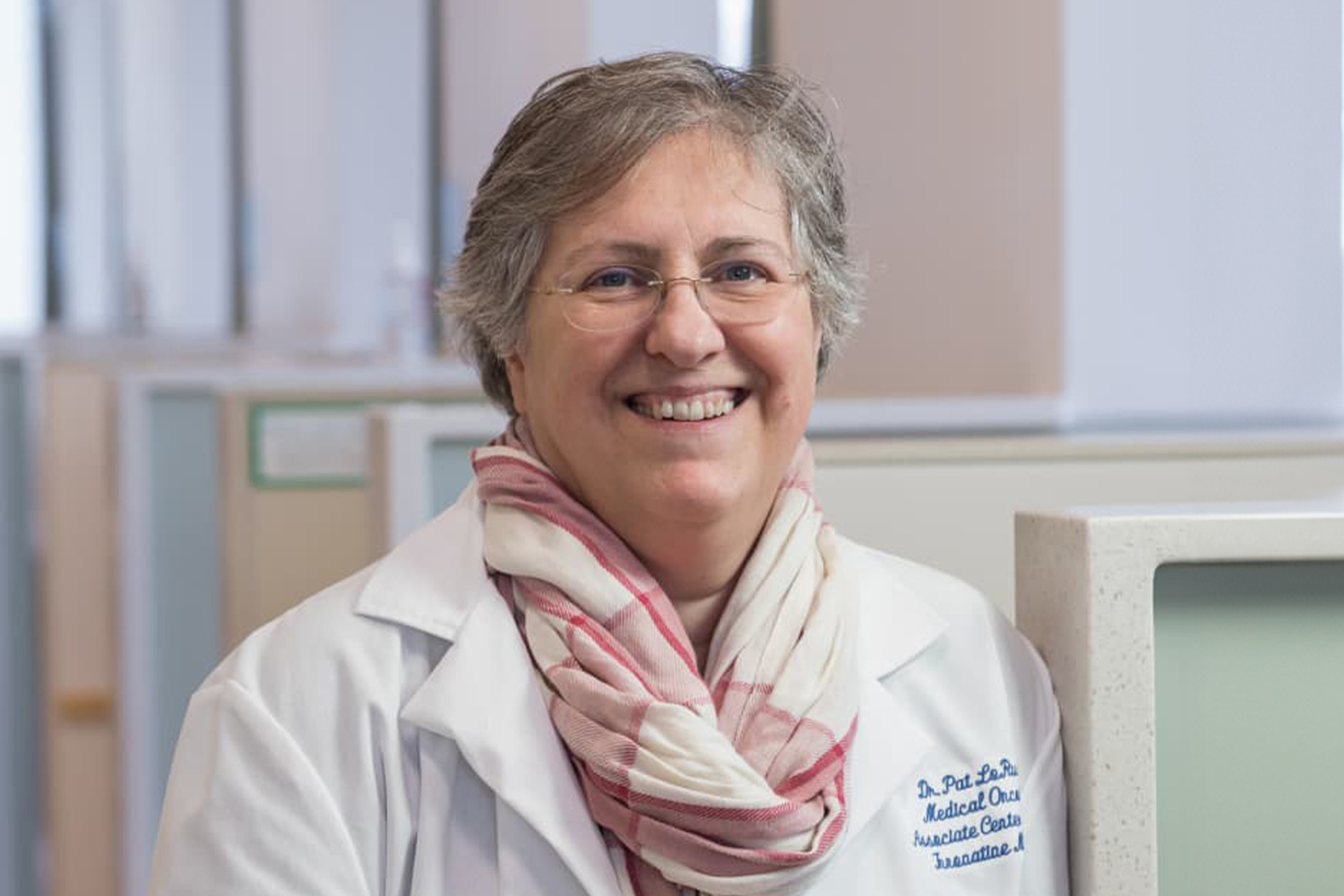

Dr. Patricia M. LoRusso: Making Clinical Trials Better

The newly inducted AACR president has witnessed major transformations in drug discovery and development.

Patricia M. LoRusso, DO, PhD (hc), began her medical career in early-phase clinical trial development to test new cancer therapies. Thirty years later, this American Association for Cancer Research® (AACR) president is still conducting early-phase clinical trials to test novel ways to treat cancer.

“I tell my students all the time—patients don’t go on trials to fill our trial cohorts. Patients go on trials because they want to live longer,” said Dr. LoRusso. “So, it is our responsibility to design trials … to maximize success for patients.”

Dr. LoRusso was inducted as the AACR’s president for 2024-2025 at the AACR Annual Meeting 2024, held April 5 to 10 in San Diego. She succeeds Philip D. Greenberg, MD, who was AACR president for 2023-2024. Dr. LoRusso is a professor of medicine, chief of early-phase clinical trials, and associate cancer center director for Experimental Therapeutics at Yale School of Medicine and Yale Cancer Center in New Haven, Connecticut.

Dr. LoRusso has seen major transformations in the process of drug discovery from the laboratory to the clinic. “In the 1980s, we had few ways to molecularly measure whether a drug was hitting its target. We could only look at clinical efficacy measures,” she said. “Now, … new technologies make it possible to measure how a drug is working at the cellular level.”

Dr. LoRusso added that real-world data are increasingly used to gain new insights into how to improve the function and safety of drugs. “More than ever, drug development is a continuum. It is not only bench to bedside, but also bedside back to the bench to understand how to make the next generation of drugs more efficacious and with less toxicity.”

On a Mission

The youngest of four siblings, Dr. LoRusso grew up in Detroit. While still a teenager in the 1970s, she lost both of her parents to cancer at a time when few treatment options were available. “As a kid, I wanted to be a veterinarian, but after losing my parents, I had my path set out for me,” she said. “I knew I would be a medical oncologist. I was on a mission and just needed to figure out how to get there.”

As a high school student, she had support and encouragement from Ms. Ross, her mathematics teacher. “If I received an award or a scholarship and there was a ceremony or a dinner, she would go with me. She was absolutely wonderful,” Dr. LoRusso recalled.

The young LoRusso attended Marygrove College in Detroit on a full scholarship with a double major in biology and religious studies. “It was a very small school, but it was a fantastic community,” she said of Marygrove, which closed in 2019. After graduating in 1977, she entered an osteopathic medical school at Michigan State University in East Lansing where later, in 2015, she received an honorary PhD. “Sometimes it is not where you go, the name, but what you make of it and what you get out of it,” she said of her education. “I was lucky to have great mentors both in college and throughout my medical career.”

Early-phase Drug Development

In 1981, Dr. LoRusso graduated from medical school. She completed an internship in 1982 and a residency in 1984 at the Riverside Osteopathic Hospital, a community hospital in Trenton, Michigan. Next up was a fellowship at Wayne State University in Detroit, where she worked in the laboratory of Thomas H. Corbett, MD, MPH. Dr. Corbett specialized in the development of mouse models that are still used today to study how tumors interact with the immune system.

Dr. LoRusso also worked with her then-fellowship director, Richard Pazdur, MD, now the head of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Oncology Center of Excellence. “Between Tom and Rick, I had the best training on drug development from both the laboratory and the clinical sides,” she said.

After completing her fellowship, Dr. LoRusso stayed on at Wayne State University at the Karmanos Cancer Institute as a faculty member starting in 1988.

Initially, she joined the breast cancer team, but soon she was leading the phase I drug development program across other solid tumors.

Patients go on trials because they want to live longer. So, it is our responsibility to design trials … to maximize success for patients.”

Dr. LoRusso has led several early-stage clinical trials with poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, which are approved to treat several cancer types, including breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer. She has watched subsequent “generations” of these drugs improve over time to help more patients. “Now, more selective molecules, including AZD5305, a PARP-1 targeted inhibitor, are being tested and showing a greater therapeutic effect with fewer side effects. We’re seeing this targeted biology where initial molecules are tweaked to create next-generation, more-selective compounds that result in greater efficacy,” she said.

Dr. LoRusso has also been a major part of the progress made in developing oral MEK inhibitors and KRAS inhibitors that target the G12C mutation, which is found in some patients with non-small cell lung cancer and other solid tumors. These treatments block one of the most commonly mutated pathways cancer cells use to grow, and several of them are now approved by the FDA.

Championing Team Science

In 2014, Dr. LoRusso moved to Yale University and continued to focus on early-phase drug trials. “I’m still in the trenches, hands-on with my patients after all of these years because I think it is so important! I love phase I trials because they are a crucial transition from the lab to the clinic. You may have a potentially potent drug that will fail if you miss important signals, get the dosing wrong, or choose the wrong patients,” she said.

Most drug development now focuses on the specific targets that drive each tumor and on the immune cells that interact with the tumor, said Dr. LoRusso. Further, more and more phase I trials are testing new therapies earlier in each patient’s treatment course before their bone marrow and immune systems have been heavily taxed with other therapies. “There is also a movement to design clinical trials such that they are more conducive to the patient living as normal a life as possible, making them less time consuming. Each patient is a human being with a life and a family, and we need to respect that more,” she said.

Dr. LoRusso is enthusiastic about the future of drug development, highlighting how new technologies and collaborations are transforming drug trials. “Cancer research used to be siloed, with basic scientists not communicating with clinicians. We’ve learned how important collaboration and communication are,” she said.

“We also previously didn’t really focus on studying drug resistance in early-phase trials, but that is happening more than ever before. It is necessary to understand how the drug works and its limitations so that we can develop next-generation therapies,” she added. “We are always thinking about the next-generation drugs and learning how our current therapies work to improve

upon them.”

Presidential Initiatives

Expand AACR’s educational reach. “There are many countries around the world where cancer-related health care is compromised and where clinical trials for cancer are either non-existent or have only a minimal presence,” said Patricia M. LoRusso, DO, PhD (hc). She plans to expand the AACR’s current scope of educational workshops to more countries to train the next generation of clinical researchers around the world. “These workshops are to train fellows and junior faculty on how to design and execute clinical trials successfully and to teach them the important value of clinical research. These are phenomenal workshops, and I would like to see them expanded beyond the U.S. and Europe,” said Dr. LoRusso.

Boosting cancer research advocacy. Dr. LoRusso wants to boost the AACR’s advocacy for increased federal funding for cancer research. “I would like to see the entire community come together to advocate for more cancer research resources. It is an exciting time in translational research to help patients, and I want the AACR to continue to use its members’ skill sets to make sure we continue to bring new biology into the clinic to better patients’ lives,” said Dr. LoRusso. “As a clinical trialist, I want to use the skill set I have developed over the last 30 years to help enhance both the AACR’s education and advocacy initiatives.”