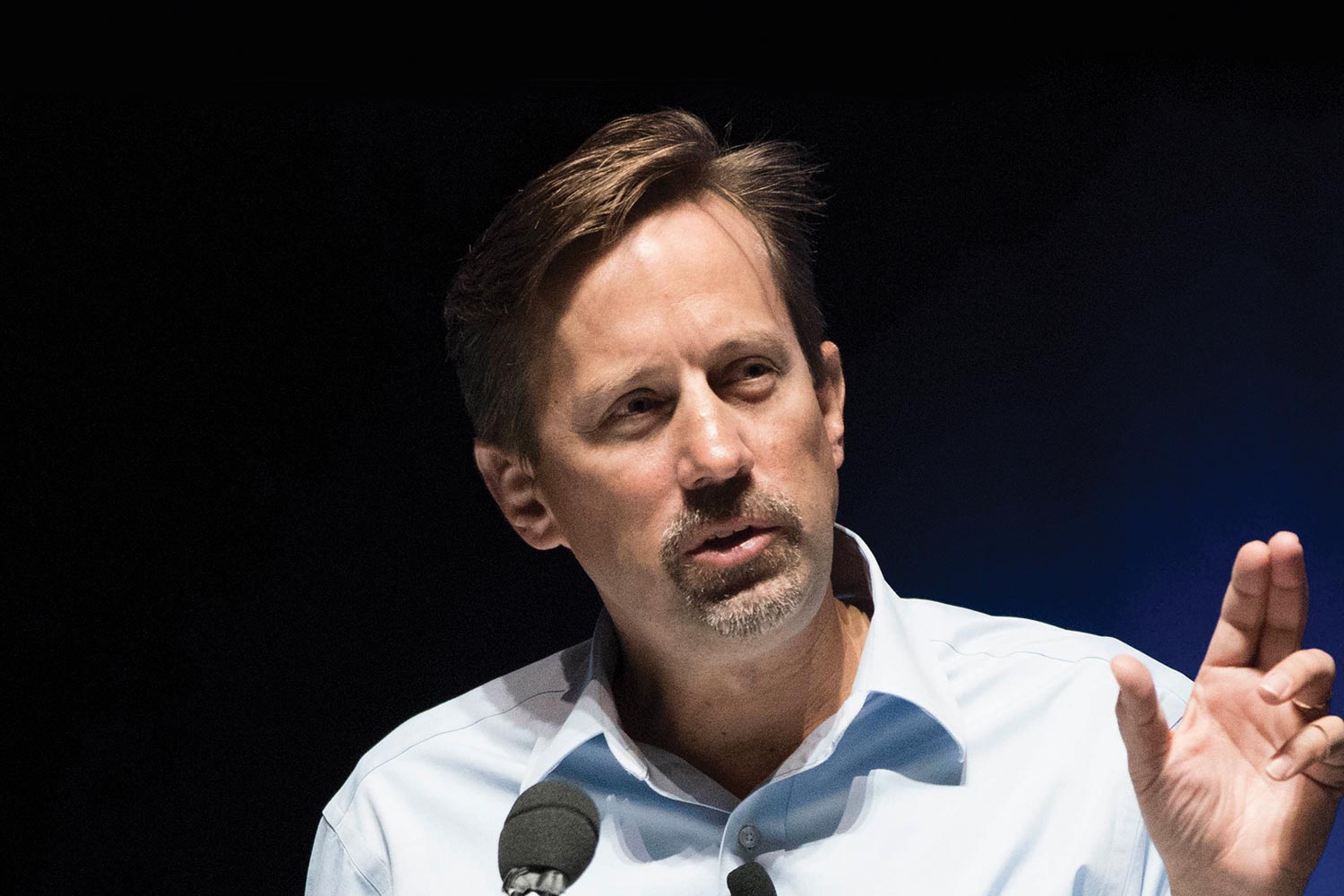

Dr. David A. Tuveson: Decoding a Complex Disease

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about many changes in our personal and professional lives. Among many other adjustments, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) has changed the way it inaugurates new presidents. For the second year in a row—following the inauguration of Antoni Ribas, MD, PhD, in April 2020—the AACR welcomed its new president virtually. David A. Tuveson, MD, PhD, is the president of the AACR for 2021-2022, after being inaugurated in a ceremony held April 12 as part of the online-only AACR Annual Meeting 2021.

In assuming the role of AACR president, Dr. Tuveson underscored the important work of his predecessor, Dr. Ribas. As an example, he cited the letter initiated by the AACR to President Joseph R. Biden, key members of his administration, and leading public health officials at state health departments urging that cancer patients be given priority in getting vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. “I hope to continue on this trajectory while president, and that with [vaccinations] and better medical treatments, we can resume some version of in-person meetings for cancer scientists,” Dr. Tuveson said.

Focused on a Cancer With Few Therapeutic Options

Dr. Tuveson has centered his clinical and research work on pancreatic cancer, a disease that is frustratingly resistant to treatment. After completing the joint MD-PhD program at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in 1994, he became a medical resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, where pancreatic cancer patients first captured his interest. At the time, new therapies were beginning to show activity in clinical trials, including imatinib (Gleevec) for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia and other treatments for patients with hematologic cancers. But the only treatments available to cancer patients with solid tumors—before the discovery of targeted treatments and immunotherapies—were the traditional methods: surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. None of them treated pancreatic cancer effectively.

After his residency, Dr. Tuveson joined the laboratory of researcher Tyler Jacks, PhD, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a postdoctoral fellow in 1997, hoping to create a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer mouse models typically harbor a genetic mutation that drives tumor formation and growth, allowing researchers to study the role of genes in cancer and the biology of how cancer spreads, and to test potential drug targets and therapies before they are tested in people.

Dr. Tuveson developed several mouse cancer models, including a lung cancer model, but a mouse model for pancreatic cancer remained elusive. When he started his own laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Dr. Tuveson finally succeeded in establishing the first mouse model for ductal pancreatic cancer. In 2006, Dr. Tuveson moved to the University of Cambridge in England to use his mouse models in developing clinical therapies for pancreatic cancer. There he met and began to collaborate with Hans Clevers, MD, PhD, whose lab had developed methods to make human organoid models of cancer. An organoid is a tiny three-dimensional cell culture that grows and self-organizes from a patient’s tumor cells. The organoid can replicate many of the complexities of a tumor in the body and has the same genetic make-up as the patient, making it useful to test potential therapies.

Currently, Dr. Tuveson is the Roy J. Zuckerberg Professor of Cancer Research and the Cancer Center director at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, as well as the chief scientist for the Lustgarten Foundation, the largest private funder of pancreatic cancer research. His lab at Cold Spring Harbor uses mouse models and human organoid models of pancreatic cancer to understand the biology of this cancer type and to inform new therapies and diagnostic techniques.

“Organoid models are exciting because they allow us to study human cancer development in a dish,” said Dr. Tuveson. His lab can make an individualized pancreatic organoid model in about two weeks and is working on reducing the time needed to one week. “The critical question is, can we make these models fast enough that we can help a patient next week? These models are very useful tools for research, but we don’t know if they will directly help inform a patient’s treatment until we understand whether we can make them more quickly.”

Successes—And Looking Out for Failures

Dr. Tuveson’s lab has recently made important inroads into understanding the biology of pancreatic cancer by seeking biomarkers in patients that can identify pancreatic disease early. The lab has also uncovered potential drug targets for therapies and is testing whether certain cellular markers may help clinicians better understand how aggressive a patient’s pancreatic cancer is or check whether a therapy is working.

For Dr. Tuveson, his successes are the fruit of lessons learned from his failures. “I encourage my team to design experiments that can fail quickly and that can refute the hypothesis, rather than support it. The experiments that can’t refute the hypothesis signal that you may be onto something.” Making sure that even failures can spur progress has become more important given the restrictions enforced during the pandemic.

“COVID-19 has led many of us in the cancer research field to become even more resourceful with our time, trainees, and ideas,” said Dr. Tuveson. With the benefit of hindsight after a year of the COVID-19 pandemic, he is quick to point out the importance of rigorous, investigational science, the failures of some governments and institutions to respond to the pandemic, and the hope for younger generations to embrace science to improve our world.

“We lost almost as many people to COVID-19 as to cancer this year in the U.S., and a lot of the COVID-19 deaths could have been prevented by a more sensible approach,” said Dr. Tuveson. “We must depoliticize the link between science and certain facets of our government, since this contributed to the chaos that descended on our population. I am hopeful that the pandemic convinces more young people to enter science and improve the world by helping stop climate change or diseases like cancer.”

Presidential Areas of Emphasis

Presidential Areas of Emphasis

As a researcher, Dr. Tuveson is unafraid to tackle complicated, multifaceted issues, and he is maintaining that approach as the AACR president. He has identified four areas of emphasis for his presidency.

Translate basic advances to improve patient outcomes. Dr. Tuveson calls for pursuing basic research in clinical oncology, including drug resistance and toxicity. The number of cancer therapies targeting intractable cancers should be expanded using chemical, genetic, biological, immunological, and computational methods. Patients with precancers should be included in clinical trials to inform the development of preventive therapies. Methods used to develop patient therapies should be redesigned and clinical trials modified to rapidly identify biomarkers of response and toxicity, including use of co-clinical trials and phase 0 trials.

Demystify cancer complexities and integrate cancer science. This requires expanding discoveries highlighting intra-tumoral genetic and epigenetic alterations by incorporating whole body approaches that include nutrition, the microbiome, and the patient’s macroenvironment. Researchers can also investigate whether tissue damage and premature aging of tissues, caused by environmental stressors and underlying germline genetics, promote formation of cancer. Dr. Tuveson calls for launching a task force on premature aging and stress and links to cancer.

Strengthen cancer research funding. Insufficient grant funding rates for researchers dampens optimism and creativity in the cancer workforce, dissuades those training or considering training from continuing in the field, and hinders research progress, Dr. Tuveson said. He wants to raise awareness of how a lack of resources prevents cancer research from occurring in disadvantaged communities. He calls for championing greater cancer research efforts globally and for fostering a universal community that collaborates in designing, developing, and distributing new and effective therapies for cancer patients.

Enhance communication to our current and future members. Improved communication is necessary, Dr. Tuveson believes, to make it clear to all that decades of basic cancer research have led to the remarkable treatment breakthroughs yielding major responses in patients with a variety of cancers. He wants to harness the AACR’s global reach and visibility to advance the large-scale translation of promising research findings into effective therapies by encouraging new memberships and partnerships. Dr. Tuveson calls for a global community of researchers who can work together as equals “to solve the cancer problem.”