Dr. Susan Band Horwitz: Decades of Work to Understand One Molecule

Her groundbreaking research to discover the properties of Taxol (paclitaxel) led to an effective cancer treatment.

In 1977, Susan Band Horwitz, PhD, was an assistant professor in the Department of Molecular Pharmacology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx borough of New York City when she received a letter that changed her life. It came from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) asking her to conduct experiments on Taxol (paclitaxel) in order to understand how the compound was able to kill cells. Taxol had been isolated from the bark of the Pacific yew tree, Taxus brevifolia, by Drs. Monroe Wall, Mansukh Wani, and their colleagues at the Research Triangle Institute in North Carolina. In 1971, these scientists published the extremely complex structure of Taxol and were intrigued by its ability to inhibit the growth of cells in tissue culture.

When Dr. Horwitz began to study Taxol, she had never heard of the compound, since there was only the single published paper that mentioned it. She and her new graduate student, Peter Schiff, received 10 milligrams of the compound and confirmed that the drug was a potent inhibitor of cell replication. They also found something startling: The new molecule interacted with microtubules, polymers within cells that provide cells with their shape and structure and are crucial for cells to divide. Additional experiments by Dr. Horwitz and Schiff revealed that the drug stabilized microtubules, paralyzing them such that the cells could not divide normally. Other anti-cancer molecules were known to prevent the formation of microtubules, but this was the first molecule that could stabilize these internal cellular structures.

“We only needed to treat the cells with a very low concentration of the drug to see its effect,” said Dr. Horwitz. “When we looked at the treated cancer cells in the electron microscope, they were just chock-full of microtubules. That was a very exciting day for us because we knew no one had ever looked in cells and seen this before,” said Dr. Horwitz. The paper describing this new mechanism of action was published in Nature in 1979.

After clinical trials in different tumor types, Taxol was first approved in the U.S. in 1992 to treat refractory ovarian cancer. Following Dr. Horwitz’s initial experiments that uncovered what Taxol does to prevent cell division, her lab continued working with the molecule, figuring out how it binds to microtubules and how slightly different forms of microtubules interact with Taxol. Dr. Horwitz studied Taxol for more than 40 years, most recently, investigating how tumors become resistant to Taxol and related anti-cancer compounds and whether that information can help predict which patients will respond to the drug.

Her meticulous work to understand how Taxol and other natural products with anti-cancer properties functioned instilled in her a “great respect for nature,” said Dr. Horwitz. When she began research on Taxol, scientists thought the Pacific yew tree synthesized the compound. More recently, researchers figured out that the now famous drug is the product of a synergistic relationship between the tree and a fungus that lives in it. “In addition to providing me with unique and architecturally complex molecules to study, trees provide food, shade, and shelter. Most importantly, they reduce the CO₂ in the atmosphere, playing an important role in climate change. Trees deserve our respect and admiration,” said Dr. Horwitz.

Discovering Biology

Dr. Horwitz entered Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania in 1954 intent on majoring in history. A mandatory biology course during her freshman year ignited her love of science. It was an exciting time. Drs. James Watson, Francis Crick, and their colleagues were uncovering the structure of DNA, marking the start of the molecular biology era. Dr. Horwitz was inspired by the science she was learning and the strong female mentors she had at Bryn Mawr. After graduating as a biology major, she applied to PhD programs in chemistry, but found that all-male faculty she encountered weren’t particularly welcoming to a potential graduate student who was a woman. “At the end of the interview, I would ask the male professor ‘Where is the ladies’ room?’ and get an initial blank stare, followed by ‘Ladies’ room? I think there might be one in the basement.’” Then she saw an advertisement for a new biochemistry department at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. She visited the school and was heartened to find two female faculty members and enthusiasm for her joining the graduate program. “I chose Brandeis, and it was one of the best decisions I made in my life,” said Dr. Horwitz.

Paving the Way for Female Scientists

Dr. Horwitz joined the laboratory of Nathan O. Kaplan, PhD, then the new chair of the biochemistry department at Brandeis, and studied the kinetics and properties of bacteria-derived enzymes. She met her husband, Marshall Horwitz, at Brandeis, and the couple welcomed twin boys a month before Dr. Horwitz received her PhD in biochemistry in 1963.

The arrival of the twins meant Dr. Horwitz had to change her plans from a postdoctoral fellowship where she was expected to work long hours. She credits Dr. Kaplan with helping her continue her academic scientific career. “He is an example of the kind of mentor I have tried to be in my career—kind, helpful, and thoughtful,” said Dr. Horwitz. Dr. Kaplan helped her find a three-days-a-week postdoc at Tufts University School of Medicine with Roy Kisliuk, PhD, in the Department of Pharmacology, which allowed her time to care for her newborns. At Tufts, Dr. Horwitz helped to teach a course on anti-cancer drugs, most of which were derived from natural products at the time. “At Tufts, I was introduced to small molecules with anti-tumor activities. I loved it and never looked back,” she recalled.

In 1967, Dr. Horwitz and her husband, a pediatrician and scientist, joined the faculty at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. “We thought we would stay for two or three years,” she said. “Instead, I learned to really love New York and stayed for 52 years!” She took on another three-days-a-week position, this time in the lab of pharmacologist Arthur Grollman, MD. Once again studying small molecules derived from nature, she became one of the first to study how camptothecin degrades DNA in cells. Camptothecin, also isolated by Wall and Wani, was found in the bark of a tree native to China and used in traditional Chinese medicine. Although the compound itself was not found to be useful in treating human tumors, two related compounds, irinotecan and topotecan, are approved for the treatment of colon and rectal cancers.

When her sons entered first grade, Dr. Horwitz switched to a full-time position. In 1970, Alfred Gilman, PhD, the chair of the Department of Pharmacology, told Dr. Horwitz he wanted to make her an assistant professor. Susan Horwitz was the first female professor in the pharmacology department and the first woman that Dr. Gilman had ever hired. Dr. Horwitz rose to full professor in 1980 and then to co-chair of the department in 1985. She stepped down in 2015, and since October 2020 has been professor emerita.

“Throughout these years, Susan provided guidance, support, and inspiration to everyone in the department. She helped the faculty get interim support when things were bad, helped them with student and postdoc problems, and assisted them in getting more laboratory and office space and equipment when they needed it,” said Jonathan N. Backer, MD, who replaced Dr. Horwitz as chairman of the molecular pharmacology department at Einstein. “But she has also played key roles in scientific policy at the national level, serving on advisory councils at the NCI and on the Advisory Committee to the director of the NIH [National Institutes of Health] as well as on external advisory committees to cancer centers at Yale University, Harvard University, Cancer Research UK Cambridge, England, and many others.”

A Life of Achievement

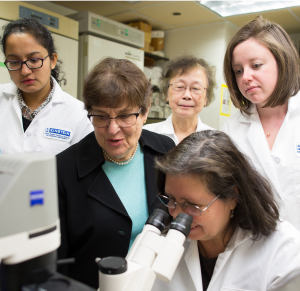

Following in the footsteps of her own mentors, Dr. Horwitz trained more than 50 graduate students and postdocs, many of whom have successful careers in both academia and the pharmaceutical industry. In 2016, to honor her contributions to the careers of young faculty at Einstein, Dr. Horwitz was awarded the Einstein Award for Faculty Mentoring.

“She provided opportunity early in my career by delegating responsibilities to me and, on occasion, permitting me to represent her at a meeting,” said Hayley McDaid, PhD, associate professor in the Department of Molecular Pharmacology at Einstein, and a former postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Horwitz’s lab. “This is one of the most important things mentors can do for female mentees—opening doors and facilitating a seat at the table.”

Dr. Horwitz served as the president of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) from 2002 to 2003. “It was wonderful to serve the AACR,” said Dr. Horwitz, who credits Margaret Foti, PhD, MD (hc), AACR’s chief executive officer, with the success of the organization. “Looking back at the history of the AACR, what is remarkable to me now is Dr. Foti and the organization’s staff insisting that female scientists participate and be represented among speakers at conferences, as chairs of meetings, and on the Board of Directors. Under Dr. Foti’s direction, the AACR was ahead of its time in encouraging women and recognizing their research and achievements. It is really impressive and important.”

Dr. Foti continues to be deeply impressed with Dr. Horwitz’s extraordinary contributions to cancer research and to the education and mentorship of young investigators. “Dr. Susan Band Horwitz is truly a pioneer and a giant in the cancer field. Her seminal experiments on Taxol led to the development of a therapy that is highly effective in treating a number of cancer types, and there are countless numbers of patients diagnosed with cancer who are alive today because of Dr. Horwitz’s innovative work,” Dr. Foti said. “It was an honor to support her efforts when she was elected as the seventh female president of the AACR, a position she held with expertise, commitment, and distinction. She was and is a role model, mentor, and inspiration to scores of cancer researchers, both male and female.”

Throughout her career, Dr. Horwitz has been widely recognized for her scientific achievements. She was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2005. In 2008, the American Cancer Society awarded her its highest prize, the Medal of Honor. The AACR honored Dr. Horwitz with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011, and she was elected a Fellow of the AACR Academy in the inaugural class of 2013.

In 2019, Dr. Horwitz was honored with the Canada Gairdner International Award for her work uncovering the exact way Taxol inhibits cells from dividing—a previously unknown mechanism for any drug—which has played a major role in the widespread use of the drug to treat cancer patients. Most recently, she received the Szent-Györgyi Prize for Progress in Cancer Research in 2020.

In 2019, Dr. Horwitz was honored with the Canada Gairdner International Award for her work uncovering the exact way Taxol inhibits cells from dividing—a previously unknown mechanism for any drug—which has played a major role in the widespread use of the drug to treat cancer patients. Most recently, she received the Szent-Györgyi Prize for Progress in Cancer Research in 2020.

Dr. Horwitz also finds personal fulfillment in her family and friends, and in her passion for the arts and nature. “As a postdoc, I remember hearing a journalist ask Susan about her greatest source of pride in life. Expecting her to respond that it was her contributions to the development of Taxol, I was taken aback when instead she said, ‘my children,’” Dr. McDaid recalled. “Despite her success and commitment, she has always demonstrated her love of family and friends, and their importance in her life.”

Looking back, Dr. Horwitz said that it was because of understanding mentors and heads of departments that she was able to find a balance between research, family, and personal relationships. “I was able to do what I did because there were people who were flexible and allowed me to work on a schedule that worked for me and my family,” said Dr. Horwitz. Being flexible for anyone who sincerely wants to work, but has a life situation not conducive to spending long hours in the lab or at an office, is something our society needs to embrace, she added.