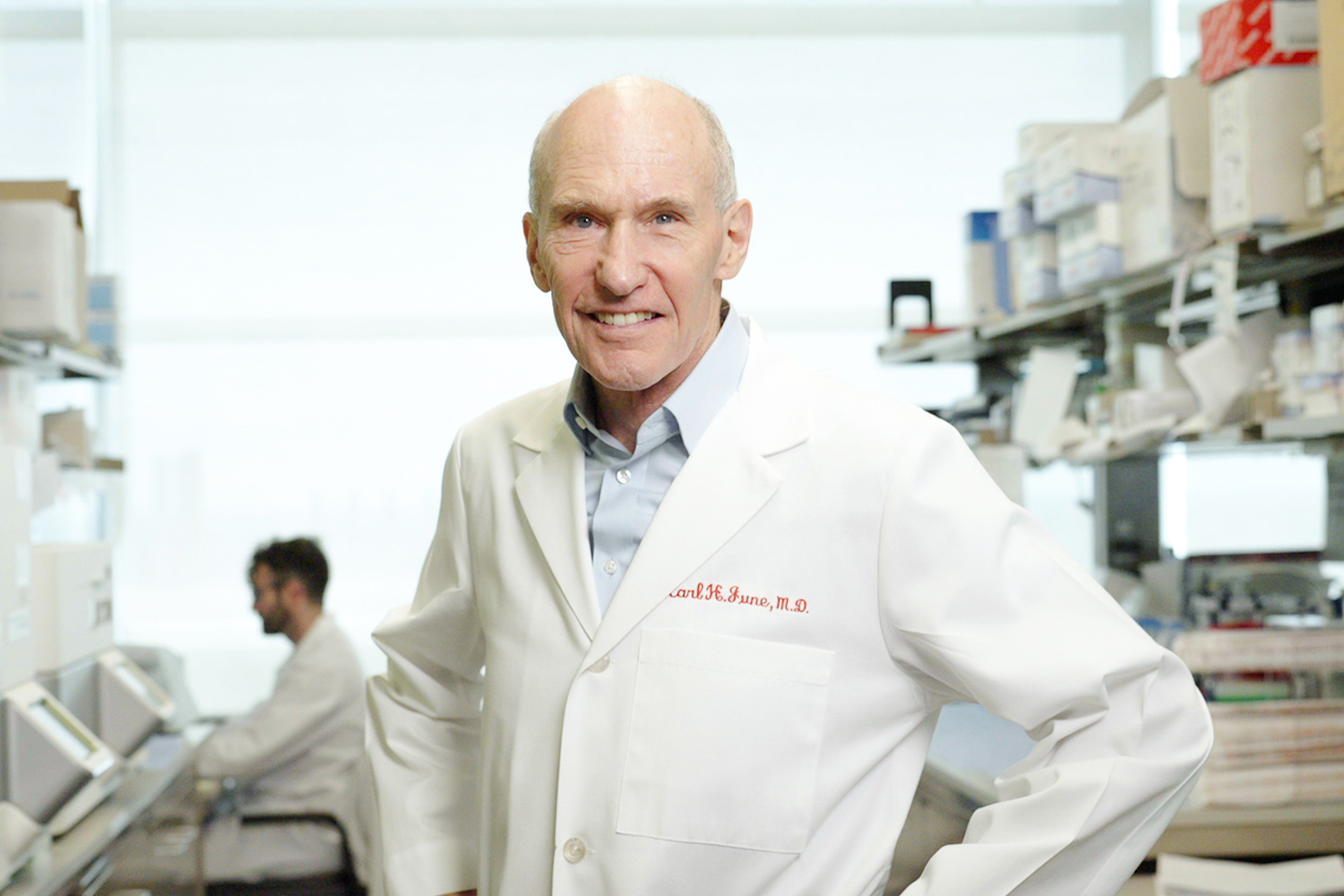

Dr. Carl H. June: Forging a Path for Cancer Cell Therapy

The renowned physician-scientist studied bone marrow transplantation and cellular therapies for people with HIV early in his career. Those experiences were followed by the dramatic development of CAR T-cell therapies for treating certain blood cancers.

Carl H. June, MD, grew up in a family of engineers. While attending high school in the San Francisco Bay Area, the young June thought he would follow in his father’s footsteps and become a chemical engineer. But in 1971, with the Vietnam War still raging, June faced the prospect of being drafted into the Army. Instead of accepting an offer to attend Stanford University, he instead enrolled in the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

As a new midshipman in 1971, June joined the academy’s second-ever pre-medicine cohort. He had excelled in biology in high school, and his interest turned to medicine when he witnessed his mother’s struggle with lupus. By the time he graduated from the academy and was commissioned an ensign in 1975, the war in Vietnam had subsided. June entered medical school—paid for by the Navy—at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. “I was fascinated by human disease and physiology and started taking graduate immunology courses while in medical school,” he said.

Dr. June graduated from medical school in three years, and in 1978, he headed to the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, on an immunology scholarship to conduct research on malaria vaccines, a focus for the Navy. Until 1996, when he left the service, his research direction would be driven by a combination of his own interests and those of the Navy.

Dr. June decided early in his medical training to concentrate on translational research, applying findings from basic research to benefit people. “I really fell in love with research, and I found I could have more impact in the clinic this way,” he said.

His focus on translational research ultimately led him and his team to develop among the first engineered cell therapies for cancer—chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells, which are now approved to treat adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and multiple myeloma and children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Today, Dr. June is a professor of immunology at the University of Pennsylvania and the director of both the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies and the Parker Institute for Cancer Therapy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia. He has been a member of the American Association for Cancer Research® (AACR) since 2000 and continues to develop CAR T-cell therapies, including ones intended to treat solid tumors.

A Passion for Research

In 1980, Dr. June continued his medical education with a four-year residency at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. In 1983, the Navy sent Dr. June to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle to learn how to perform bone marrow transplants. It was still the Cold War, and the Navy wanted Dr. June to open a bone marrow transplant clinic at the Bethesda Naval Hospital to treat potential radiation casualties.

The Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, often called the Hutch, was among the world’s first dedicated translational medicine centers and among the best clinics dedicated to bone marrow transplantation. “It was the cat’s meow to be able to go there,” Dr. June recalled. After a year of performing bone marrow transplants on patients at the Hutch, Dr. June jumped head first into laboratory research. By closely working with his mentors at the Hutch, he learned how to manipulate T cells and published his first academic papers. Monoclonal antibody technology had just become available in 1979, and Dr. June set out to understand how antibodies worked. A colleague happened to be working with antibodies against CD28, a protein found on the surface of T cells that serves as a co-receptor for the cells’ activation. With access to this antibody, June and his mentors found that the anti-CD28 antibodies could stimulate T-cell growth and figured out a T-cell culture system. T-cell biology was still in its infancy and culturing T cells in the lab was no easy feat, but Dr. June and his colleagues created among the first ways to grow and expand the number of T cells outside the body.

At the Hutch, Dr. June learned an important lesson in how to succeed in scientific research. His mentors were immunology and genetics experts, but he needed to understand how to apply biochemical techniques to study the anti-CD28 antibody. Dr. June sought out the expertise of biochemist and Nobel laureate Edwin G. Krebs, MD, PhD, at the University of Washington in Seattle and spent three months in his lab learning these techniques, including how to conduct immunological assays to characterize which molecules an antibody binds to and to what degree. “I found out early in my career the power of bridging the expertise of different laboratories and taking yourself out of your comfort zone,” Dr. June reflected.

It’s an exciting time. We have the tools coming together now for even better immunotherapies. … Now, there is rapid progress with real paradigm shifts that are happening and moving the field forward.

– Carl H. June, MD

He returned to Bethesda in 1986 to start a lab at the Naval Medical Research Institute, this time to focus on infectious disease. “I didn’t have to worry about funding. It was awesome. I was a complete lab rat working all the time. I went from an MD to a mouse doctor, seeing fewer and fewer patients,” he said, referring to the practice of using mice in lab research.

Engineering T Cells

Dr. June continued to study T-cell biology, but this time, the Navy directed his focus to rebuilding the immune system of those with human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 (HIV-1). Dr. June’s approach was to amplify the patient’s T cells in the lab using the anti-CD28 antibody-based culture system he and his colleagues had developed. Once amplified, the T cells would be returned to the patient’s body to replenish the T cells destroyed by the HIV-1 infection.

In 1992, Bruce L. Levine, PhD, joined Dr. June’s laboratory to work on projects that included T-cell activation and growth in healthy and HIV-positive donors. Together, the two researchers created a novel reagent that would later serve as the genesis for Dr. June’s work on CAR T-cell treatment for cancer. Dr. June and Dr. Levine, now a professor in cancer gene therapy at the University of Pennsylvania, coated microscopic beads with anti-CD28 antibodies and anti-CD3 antibodies, which the team found are two key ingredients to stimulating efficient T-cell growth outside the body. The two also discovered, by accident, that if a patient’s T cells were activated by these two bead-bound antibodies instead of soluble anti-CD28 antibodies, the T cells unexpectedly became resistant to HIV-1 infection. The results were published in the journal Science in 1996 and 1997. “Serendipity has been a big part of my lab as it turns out!” Dr. June said.

Following publication of the new technology, a now-defunct biotechnology company in California, Cell Genesys, came to Dr. June, offering to test his T-cell growth method in a trial of CAR T cells in patients with HIV-1. “You needed an efficient way to grow T cells from the patient herself, and we happened to stumble upon a completely novel, physiological, and efficient way to do this using the beads we developed with Bruce Levine,” Dr. June recalled.

Dr. June and his colleagues created the first engineered CD8+ T cells, which he dubbed CAR T cells, to attack the CD4+ helper T cells, where the HIV-1 virus replicated. In the first three CAR trials in HIV-1 patients who had a low T-cell count, the T-cell therapy resulted in an increased T-cell count and better immune function, but the cellular therapy turned out to be only mildly effective. By then, in 1997, promising oral therapies for treating HIV-1 were in development, and the CAR T-cell approach was abandoned.

Turning CAR T Cells On to Cancer

Dr. June was trained as a leukemia specialist in the 1980s, but while serving in the Navy, he couldn’t turn his focus to cancer. Then, in 1996, his wife was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. “My cancer training became front burner for me then,” he said. Working with cancer investigators at the University of Maryland and the University of Chicago, Dr. June’s lab made T cells from patients’ own bodies to treat leukemia, but initially without the CAR genetic modification. One of the patients treated this way in a clinical trial went into remission and is still cancer-free 20 years later. Unfortunately, Dr. June’s wife, Cynthia, died from ovarian cancer in 2001.

Having left the Navy in 1996 and wanting to focus on cancer, Dr. June moved to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia to establish a human immunology program, manufacture human T cells, and conduct clinical trials. At the time, only a handful of laboratories were working on immunotherapy, which was not seen as a promising avenue for treating cancer. But Dr. June persevered, funding his lab via philanthropy rather than the National Cancer Institute.

After initial trials in which leukemia patients’ own T cells were expanded in number using the bead technique that he and Dr. Levine had developed, Dr. June’s lab began to extract T cells from cancer patients, genetically re-engineer them to express CARs, and expand their number outside the body. A new postdoctoral researcher in the June lab, Michael C. Milone, MD, PhD, now an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania, developed an optimized CAR-targeting CD19, a protein found only on B cells, including cancerous B cells. The CD19 CAR T cells targeted the CD19 antigen on malignant B cells, and Dr. Milone developed a version of the CAR T cell that efficiently grew and persisted in patients and potently killed leukemia cells. The work, published in Molecular Therapy in 2009, provided a crucial blueprint for selecting and testing CAR T cells in the clinic, and ultimately this CAR version became the currently commercialized CAR T-cell therapy Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel), manufactured by the pharmaceutical company Novartis.

In 2010, Dr. June, David L. Porter, MD, a hematologist-oncologist at the University of Pennsylvania, and their team treated three adults who had refractory CLL with the CD19-targeted CAR T cells. Pediatric oncologist Stephan Grupp, MD, PhD, successfully treated the first pediatric patient, who had refractory ALL, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in 2012.

Shortly after the initial treatment of adult patients was reported, Novartis licensed the June lab’s CAR T-cell intellectual property to manufacture CAR T cells commercially. “Suddenly, biotechnology companies were very interested when they had not been before,” Dr. June recalled. “Now, there are hundreds of companies developing CAR T cells.”

Solid Tumors: The Next Frontier

Today, Dr. June’s lab is developing CAR T-cell therapy for solid tumors. “We are just starting to see responses in patients with solid tumors, which have been more difficult to target effectively, compared with blood cancers,” he said. A major issue in treating solid tumors with CAR T cells is getting access to the tumor due to the anatomy of the organ where the tumor is located and a fortress of scar and connective tissue that frequently surrounds the tumor.

Dr. June is also taking advantage of recent gene-editing technology to increase the effectiveness of CAR T cells. In 2020, his lab published results from the first-in-human trial of engineered T-cell editing using the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing system. The small study found that the CRISPR-modified T cells survived in patients long term and demonstrated the feasibility of using this approach in larger studies. His lab is now focused on CAR T-cell trials for pancreatic and ovarian cancers—among the most difficult tumor types to treat.

Dr. June is buoyant about the future of immunotherapy. “It’s an exciting time. We have the tools coming together now for even better immunotherapies,” he said. “The idea of using the immune system to treat cancer is 100 years old, and it failed and failed because we didn’t understand how to harness it. Now, there is rapid progress with real paradigm shifts that are happening and moving the field forward.”

Teaching and Inspiring Young Cancer Researchers

When Dr. June began his cancer immunotherapy research in the 1990s, it was difficult to attract students to what was then perceived as an unpromising field. Now, among the best cancer researchers are entering the field.

Dr. Levine, who worked with Dr. June in the 1990s, initially read his papers on T-cell activation as a graduate student and was inspired by them. In the early 2000s, when Dr. Milone was working with Dr. June, other mentors expressed doubts that immunotherapy could work. “But I thought that there was tremendous opportunity for gene and cell therapy in human disease, and … I wanted to do research that was close to patients and exciting,” Dr. Milone said. “Dr. June was one of the people doing this [kind of research]. When I met with him, I felt I shared his vision of moving rapidly between the lab bench and the clinic. He modeled what I hoped to become.”

Dr. June is supportive of his students and postdocs but sets high expectations and models the work ethic he expects, Dr. Milone added. “Carl is probably the most committed scientist I know,” he said. “When I was a clinical fellow right before joining his lab as a research postdoc, I had the unfortunate opportunity to see him in the hospital when he visited his wife, who was dying of ovarian cancer. I saw his devotion as a husband, and I also saw how this experience drove him and deepened his commitment to developing new therapies for cancer. He is on a journey, and I will say that I feel blessed to have had the opportunity to be a part of that journey.”

A Commitment to Teaching Through the AACR

Dr. June served as a member of the AACR Board of Directors from 2018 to 2021. He has been a vice chair and co-chair of the AACR Annual Meeting Program Committee and has filled editorial roles on AACR journals.

In 2015, Dr. June was honored with the AACR-Cancer Research Institute Lloyd J. Old Award in Cancer Immunology and, in 2017, was elected a Fellow of the AACR Academy. In 2023, he received the AACR Award for Lifetime Achievement in Cancer Research. In September 2023, it was announced that Dr. June would share with Michel Sadelain, MD, PhD, a $3 million Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for his work on CAR T-cell therapy. Breakthrough Prizes are annual awards presented in the sciences and math by a group of major tech industry leaders.

Dr. June continues to mentor and teach. For the AACR, he has participated in an annual weeklong education program for cancer researchers transitioning from postdoctoral researchers to running their own laboratories as principal investigators. The program offers courses taught by Dr. June and others on running a laboratory, mentoring graduate students and postdocs, and other skills not formally taught to scientists during their graduate and postdoctoral studies.

“It’s a fabulous, intensive lecture series that brings together some of the best oncology leaders and the next generation of oncology researchers,” he said. “Some of the students I taught are now coming back as faculty members to teach. This is a fantastic community that comes back full circle, thanks to the AACR.

“The AACR has taken a leadership role in promoting and championing immuno-oncology, and that has been wonderful to see,” Dr. June added.