Research Updates

AACR® journals and scientific meetings boast groundbreaking cancer research.

Genetic Ancestry May Play a Role in Prostate and Breast Tumor Biology

In a pair of studies presented at the 15th AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, held September 16-19 in Philadelphia, Clayton Yates, PhD, of Tuskegee University in Alabama, and colleagues reported that certain genetic variants found in prostate tumors of men of African descent were associated with African ancestry. Dr. Yates also chairs the AACR Minorities in Cancer Research Council.

In a pair of studies presented at the 15th AACR Conference on the Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, held September 16-19 in Philadelphia, Clayton Yates, PhD, of Tuskegee University in Alabama, and colleagues reported that certain genetic variants found in prostate tumors of men of African descent were associated with African ancestry. Dr. Yates also chairs the AACR Minorities in Cancer Research Council.

In one study, the tumors of patients with African ancestry were more likely to harbor mutations in the tumor suppressor gene SPOP compared with the tumors of patients with European ancestry. This gene is mutated in approximately 10 to 15 percent of all prostate cancers. SPOP mutations in patients with African ancestry correlated with increased expression of a pro-inflammatory immune gene signature and the immune checkpoint proteins PD-L1 and PD-1. “This is an exciting discovery that may help identify patients who would benefit from immunotherapy, which is particularly important given that African Americans are often underrepresented in clinical trials evaluating such therapies,” Dr. Yates said.

In the second study, published concurrently in Cancer Research Communications, an AACR journal, Dr. Yates and colleagues found that genetic variants in BRCA1 and other DNA repair genes, including some not previously known to impact prostate cancer, were similar between Nigerian and African American prostate tumors. The frequency of mutations in the DNA repair gene BRCA1 increased with higher proportions of African ancestry and decreased with lower proportions of African ancestry. These findings may have implications for prostate cancer treatment in patients of African descent, Dr. Yates explained.

Women of sub-Saharan African descent have disproportionately higher triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) incidence and TNBC-specific mortality. Because of heterogenous genetic admixture and biological consequences of social determinants, African ancestry’s true association with TNBC biology is unclear.

In a third study presented at the conference and concurrently published in the AACR journal Cancer Discovery, Melissa B. Davis, PhD, from Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, and colleagues performed RNA sequencing of an international cohort of West African/Ghanaian women, East African/Ethiopian women, and African American women with TNBC, and found associations between African ancestry and the immunological landscape of TNBC. This may explain some differences in race-group-related clinical outcomes among patients with TNBC, the researchers note.

Durability of BCMA CAR T-Cell Therapy Response May Be Influenced by Tumor Microenvironment

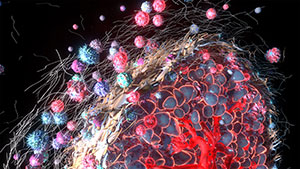

A study published in Blood Cancer Discovery, an AACR journal, showed specific components of the tumor microenvironment may influence responses from a type of CAR T-cell therapy that targets the protein BCMA. Patients with myeloma whose tumor immune microenvironments had a more diverse baseline T-cell repertoire, fewer markers of immune cell exhaustion, and distinct changes to immune cell populations were more likely to have longer progression-free survival (PFS) after treatment with BCMA-targeted T-cell therapy.

A study published in Blood Cancer Discovery, an AACR journal, showed specific components of the tumor microenvironment may influence responses from a type of CAR T-cell therapy that targets the protein BCMA. Patients with myeloma whose tumor immune microenvironments had a more diverse baseline T-cell repertoire, fewer markers of immune cell exhaustion, and distinct changes to immune cell populations were more likely to have longer progression-free survival (PFS) after treatment with BCMA-targeted T-cell therapy.

In this study, researchers analyzed pre- and post-treatment bone marrow samples from 11 patients who had clinical responses to BCMA-targeted CAR T-cell therapy. They found that in patients with long PFS, the proportion of T cells in the bone marrow increased after treatment, while the proportion of myeloid cells decreased. These changes were not observed among patients with short PFS. A higher proportion of myeloid cells may have contributed to recurrence in the patients with short PFS by promoting cancer growth or suppressing antitumor immunity, said study author Madhav Dhodapkar, MBBS, from Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta.

Compared with post-treatment T cells from patients with short PFS, those from patients with long PFS had a distinct genomic signature with lower expression of immune checkpoint genes and other genes associated with T-cell exhaustion.

“The major finding of this study is that the durability of response may be dependent on characteristics of non-CAR T cells and other immune cells in the tumor microenvironment,” said Dr. Dhodapkar, noting prior studies on response durability tended to focus on features of the CAR T cells themselves. “This finding has broad implications for the CAR T-cell therapy field, as it emphasizes the importance of the patient’s preexisting immune microenvironment as a determinant of durable responses.”

Researchers Debate if DCIS Should Be Called Cancer and if It Should Be Treated With Radiotherapy

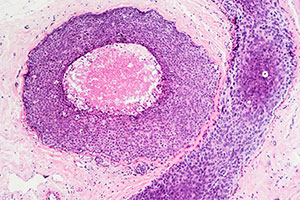

The AACR hosted a special conference titled “Rethinking DCIS: An Opportunity for Prevention?” in Philadelphia September 8-11. DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ) is a pre-invasive breast lesion usually detected through a routine mammogram. It accounts for about 25 percent of all newly diagnosed breast cancer cases in the United States. Some estimates suggest that, if left untreated, up to 40 percent of DCIS cases will progress to invasive cancer during the patient’s lifetime.

The AACR hosted a special conference titled “Rethinking DCIS: An Opportunity for Prevention?” in Philadelphia September 8-11. DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ) is a pre-invasive breast lesion usually detected through a routine mammogram. It accounts for about 25 percent of all newly diagnosed breast cancer cases in the United States. Some estimates suggest that, if left untreated, up to 40 percent of DCIS cases will progress to invasive cancer during the patient’s lifetime.

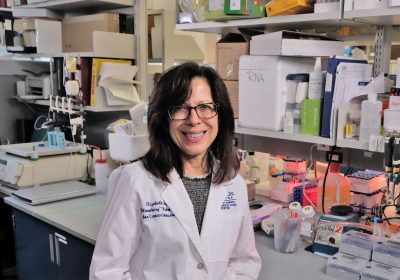

“Despite its prevalence, there is still much to learn about this disease,” Kornelia Polyak, MD, PhD, from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and one of the meeting’s co-chairs, said in an interview. “We do not yet have a clear understanding of why some DCIS cases progress to invasive breast cancer and others do not. As a result, the treatment approach is not very standardized, with some undergoing a lumpectomy, others a complete mastectomy, and some even receive systemic therapy.”

During the conference, experts debated whether DCIS should be classified as cancer and whether it should be treated using radiation therapy.

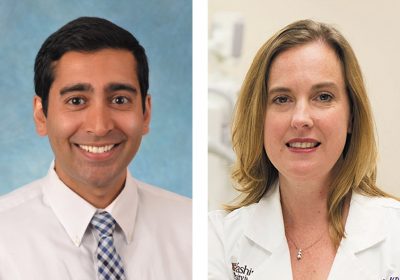

Jennifer Marti, MD, from Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, argued DCIS is a risk factor for cancer and not a cancer itself, with a risk of progression similar to that of other breast hyperplasias. Steven Narod, MD, from Women’s College Research Institute in Toronto, disagreed, claiming DCIS can occasionally produce tiny micrometastases, and the prevalence of recurrence in the opposite breast indicates a propensity for DCIS to spread. Moderator Laura Esserman, MD, MBA, of the University of California, San Francisco, brought the debaters to a consensus: They agreed that some DCIS cases should be defined and treated as cancer while others could be carefully monitored, and that new biomarkers are necessary to differentiate the two populations.

In the other debate, Bruce Mann, MBBS, PhD, from the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia, claimed radiotherapy is not necessary for patients with DCIS because the risk of harmful side effects greatly outweighs the potential benefits. Nicolas Prionas, MD, PhD, from the University of California, San Francisco, argued newer radiotherapy techniques can minimize exposure to healthy tissue, thereby shifting the balance between benefit and risk. The two agreed that the risk-benefit analysis may be different for each patient and that some patients would benefit from radiation more than others. Dr. Mann and Dr. Prionas also agreed new biomarkers are crucial to determine who will benefit most.

Adolescent and Young Adult Leukemia Survivors May Have Higher Mortality Rates Than the General Population

A study published in the AACR journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention showed adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) may have higher mortality rates than the general population, decades after their diagnosis.

A study published in the AACR journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention showed adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) may have higher mortality rates than the general population, decades after their diagnosis.

Michael Roth, MD, from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, and colleagues used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to analyze mortality patterns in 1,938 ALL survivors and 2,350 AML survivors from 1975 to 2011 and compared them with a U.S. national cohort obtained from the National Vital Statistics Report.

The researchers found the 10-year survival of AYA leukemia survivors was approximately 10 percent lower than that of the age-adjusted U.S. general population, and the differences persisted for up to 30 years of follow-up. Leukemia remained the most common cause of death in the early survivorship period. “Some of these patients aren’t being fully cured of their initial cancer, so between five and 10 years post-initial diagnosis, most of the deaths are due to disease progression or relapse, whereas after that, most of the deaths result from late side effects from treatment, including cardiovascular disease and secondary cancers,” Dr. Roth said.

Older age at diagnosis correlated with worse long-term survival outcomes, with each additional year at diagnosis associated with a 6 percent and 5 percent decrease in long-term survival for ALL and AML survivors, respectively. Patients’ sex was associated with long-term outcomes only for AML survivors, with males surviving only 61 percent as long as females. Among survivors of ALL, Asian or Pacific Islanders had longer survival than Hispanics.

The researchers found long-term survival in AYA improved in more recent decades of diagnosis, as the life span of individuals diagnosed in the 1990s and 2000s was more than twice as long as that of individuals diagnosed in the 1980s. This was likely due to treatment advances leading to improved cure rates with lower toxicities and better supportive care. However, there was no further improvement in long-term survival for patients diagnosed in the 2000s compared with those diagnosed in the 1990s for either ALL or AML.