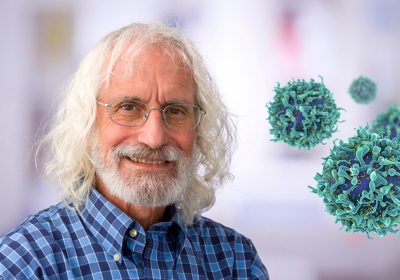

Dr. Phillip A. Sharp: Collaboration Is the Key to Progress

Not many people can say they’ve won a Nobel Prize and been featured on the side of a jetliner with Avengers superheroes. Phillip A. Sharp, PhD, can check both boxes. And that’s just a small sample of his many extraordinary achievements.

The throughline of Dr. Sharp’s career, which spans nearly half a century, is his commitment to developing collaborations that can generate new ways of thinking about cancer. His dedication to forging connections was on display in October, when he led the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) 30th Anniversary Special Conference on Convergence: Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and Prediction in Cancer. Convergence refers to efforts to extend transformative insights and innovations from fields like computer science, physics, and engineering into the life sciences, especially cancer science.

Dr. Sharp netted the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his co-discovery of RNA splicing, but he didn’t set out to be a cancer researcher. He entered a doctoral program in chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and received his degree in 1969. It was during his postdoctoral training in 1970 at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena that he made the transition from being a physical chemist to studying biological processes in bacteria. “I decided it would be an interesting opportunity to study the structure and expression of genes, and with that, changes in the expression of genes, which are an integral part of the cancer process,” he said.

In 1971, that career choice brought him to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, the prestigious international research institution focused on molecular biology and genetics in Cold Spring Harbor, on Long Island in New York. There, Dr. Sharp worked with James Watson, PhD, who had been awarded the Nobel Prize in 1962—along with Francis Crick, PhD, and Maurice Wilkins, PhD—for identifying the structure of DNA. In 1974, Dr. Sharp accepted a position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, where he continued to study the DNA tumor viruses he had focused on at Cold Spring Harbor. At the time, it was widely believed that every gene was made up of connected base pairs. In 1977, while studying a cold virus, Dr. Sharp made a discovery that turned this idea on its head: Genes could be “split” into several separated segments. For the impact this finding had on biomedical research, Dr. Sharp and Richard J. Roberts, PhD, received the Nobel Prize.

Dr. Sharp flourished at MIT. When he arrived, its Center for Cancer Research (now the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT) had just been established by Salvador Luria, MD, who had won a Nobel Prize in 1969 for research on the genetic structure of viruses. It was a heady time. “There were four of us who received Nobel Prizes and several others who could have,” said Dr. Sharp. “It’s been a remarkably exciting and dynamic research community. We were able to lay down some of the most powerful principles in cancer research.” Dr. Sharp served as the director of the research center from 1985 to 1991. Today he is an Institute Professor—the highest academic ranking a professor can receive.

For his major contributions to cancer science, Dr. Sharp was elected as an inaugural Fellow of the AACR Academy in 2013. He has nothing but praise for the AACR. “It’s a tremendous convening and communication organization,” he said. “The Annual Meeting offers an opportunity to interact with people from around the world interested in cancer, cancer research, and cancer clinical care. It’s a remarkably powerful, intellectual, consensus-driven organization.”

Upon Dr. Sharp’s receipt of the 2018 AACR Distinguished Award for Extraordinary Scientific Innovation and Exceptional Leadership in Cancer Research and Biomedical Science, Margaret Foti, PhD, MD (hc), AACR Chief Executive Officer, said, “During his illustrious career, Dr. Sharp has consistently manifested extraordinary dedication to the AACR and its mission. He has provided sage advice and counsel to the AACR on numerous important issues, and his loyalty to our organization continues to this day.”

Keeping Busy With Stand Up To Cancer

Dr. Sharp is the chair of the Stand Up to Cancer (SU2C) Scientific Advisory Committee, a position that includes overseeing the selection of SU2C Dream Teams and other research teams and presiding over its annual Scientific Summit, along with his vice chairs. The AACR has served as the esteemed Scientific Partner of SU2C since the organization’s inception in 2008, managing scientific peer review and handling administration and scientific oversight of research grants funded by SU2C and also jointly with its collaborators.

SU2C was founded in 2008 by nine women—movers and shakers in the film and broadcasting industries who had been personally affected by cancer. From the outset, the women knew they wanted Dr. Sharp to chair the Scientific Advisory Committee, said SU2C co-founder Sherry Lansing, a former CEO of Paramount Pictures and the first woman to head a Hollywood movie studio. “Everyone who we talked to told us, if you can get Phil Sharp, with his integrity, you will be able to attract all of the scientists you want,” she recalled.

When SU2C’s founders heard that Dr. Sharp would be at the upcoming AACR Annual Meeting, Lansing said, “we all went to the dinner meeting we knew he would be attending and descended on him.”

The AACR and Dr. Foti played a pivotal role in bringing together Dr. Sharp and SU2C. With Dr. Sharp at the helm and the AACR’s organizational staff support and scientific credibility, the recruitment of leading translational cancer researchers, physician-scientists, and patient advocates as members of the Scientific Advisory Committee was greatly facilitated.

Dr. Sharp said he was very surprised that the SU2C founders wanted him to lead the committee. He was intrigued, however, not only because they were positioned to bring together the media, the public, and science, but also because they wanted to spur collaboration across different scientific disciplines.

“I said this is something I basically have to do,” said Dr. Sharp. “I didn’t need another job, but I had to do this, because it was so important for cancer research and for patients. And it’s been a lot of fun.” Part of the fun is having his image featured alongside Marvel Comics superheroes Captain America, Doctor Strange, and others on an American Airlines jet. The plane, unveiled in April, promotes a collaboration of SU2C, American Airlines, and Marvel to raise money for cancer research.

Through his work with SU2C, Dr. Sharp has been able to demonstrate the power of collaboration. He has overseen the selection of 24 Dream Teams and numerous other grants and awards that bring together scientists from different disciplines and institutions. Dr. Sharp says working together makes sense. “We can have the theory and then go to the clinic and test it to see if we are correct—and we can do it in a year or two,” he said. “It’s just remarkable what we can do if we can get everyone to talk together.”

Discussing the AACR’s role as SU2C’s Scientific Partner, Dr. Foti said, “The AACR has had a spectacular vantage point to witness how Dr. Sharp embraces the urgent need for collaboration in cancer research. He has translated his considerable scientific expertise into a dynamic leadership role in cancer science that stimulates innovation and encourages other scientists to bring their best original work to the goal of defeating cancer in all its forms.”

Looking to the Future

In 1988, Dr. Sharp organized the AACR’s first special conference in cancer research. That meeting, which focused on gene regulation and oncogenes, drew attention to rapid advances in biochemical analysis of proteins that regulate transcription, the first step of the process in which a segment of DNA is copied into RNA. That meeting has been characterized as a watershed event in stimulating novel, transformative thinking about the molecular biology of cancer.

Today, Dr. Sharp sees a similar potential in the power of convergence science. Sitting at the intersection of physics, engineering, artificial intelligence, big data, and life sciences, it is inherently built on collaboration. In short, said Dr. Sharp, “it brings the future to cancer research.”

“What we know about cancer now is that each cancer in a patient is heterogeneous,” Dr. Sharp explained. “Cancer cells have different types of mutations. To understand the complexity of a cancer, we need to capture as much information about its specific mutations and gene changes and heterogeneity and immune cell infiltration as we can, so we can match our therapies to the cancer and reduce cancer deaths.”

But finding and honing new treatments is only one way this data can be used. Dr. Sharp and others believe new technologies and analyses of vast data sets will help us better identify those at highest risk for specific cancers who would benefit most from cancer screening tests. It’s also at this convergence of sciences and with collaboration across disciplines that researchers will be able to find answers to especially prickly problems, like which prostate, breast, or thyroid tumors can be deadly and need immediate treatment and which ones can be watched for further changes.

Dr. Sharp is confident all of this is within reach. What’s necessary now, he said, is “to create the environment and research support and momentum to make it happen as fast as we can.”

It’s hard to think of anyone better than a Nobel prize-winning superhero to lead the charge.